The Structural Model of Crystal Eye takes shape

Before a new scientific instrument can venture into space, it must successfully pass a long series of trials. It’s not enough for it to simply function well: it must also survive the launch, which is notoriously a “traumatic moment” in the "life" of any object destined for space. This is where the Structural Model of Crystal Eye enters the scene—a “silent twin” of the detector, built specifically to undergo the essential testing that prepares it for subsequent launch activities.

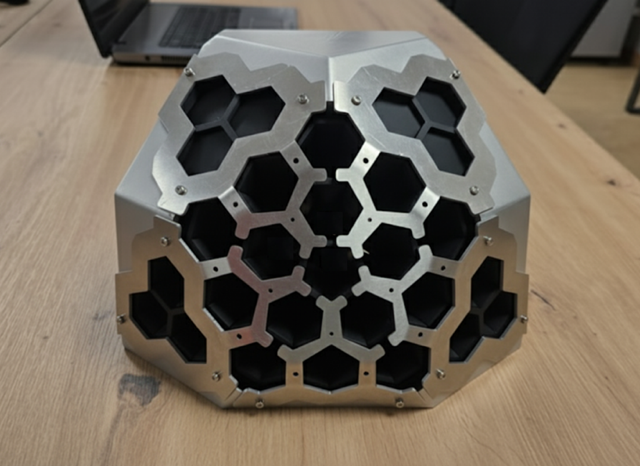

This rigorous “stress test” will serve to understand exactly how the future instrument will react to the vibrations of the launch and to identify any potential structural weak points. The team from Astra's WP1 (Advanced technologies for Space industry) has completed the assembly — the joining of parts — of the Crystal Eye structural model. “Given the nature of the tests to be carried out,” states GSSI researcher Felicia Barbato, “not all the standards and requirements typically adopted for the production of qualification and/or flight components were strictly applied to the manufacturing of these parts. However, the materials used are of an equivalent nature to those that will be employed in the subsequent versions of the detector.” The structural model, therefore, is nothing more than a non-functional but completely identical copy of the real Crystal Eye, as can be seen from the photo below (referencing the original article), which shows the internal structure.

In the next photo (referencing the original italian article), however, we can identify the two principal parts: the load-bearing structure, which will contain the crystals destined to detect gamma rays, and the Electronics Box, the operational hub that interprets the signals received by the detector and communicates with the satellite to send data back to us.

The detector's support structure is made entirely of aluminum and is composed of main sub-parts, represented by internal and external semi-sphere sections. The load-bearing structure is composed of two hemispheres, one internal and one external. Within it are the crystals and electronics which, in the operational version, will record particles and radiation-related phenomena. In the structural model, all of this is simulated, but the support structure is, of course, identical to the flight structure. There is also the “Electronics Box,” also made of aluminum, which will host the circuit boards and systems that process the data.

Once completed, numerous accelerometric sensors will be positioned on the model. During the vibration test, these sensors record precisely how the instrument moves and reacts to shocks and movements. This real-world data will then be compared with computer-generated simulations. In short, these are fundamental test steps designed to guarantee the ultimate reliability and trustworthiness of the actual Crystal Eye, which represents one of the key pillars of the Astra project.